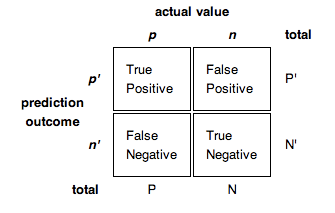

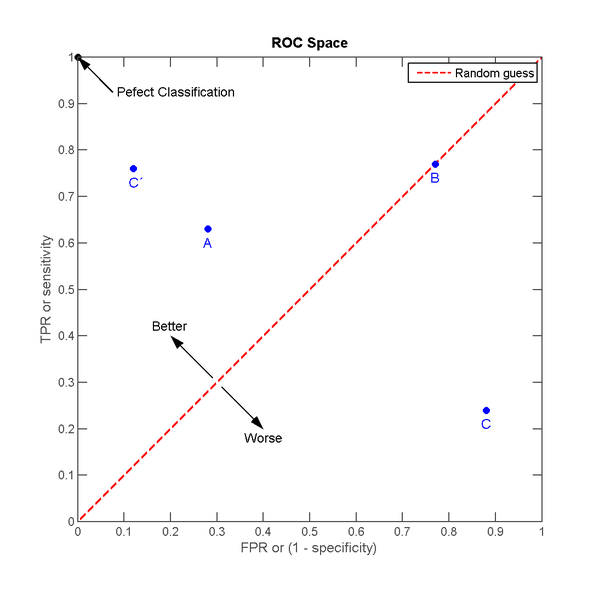

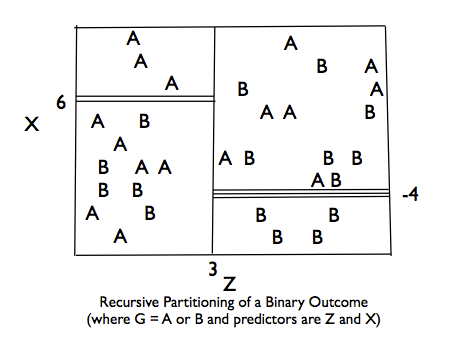

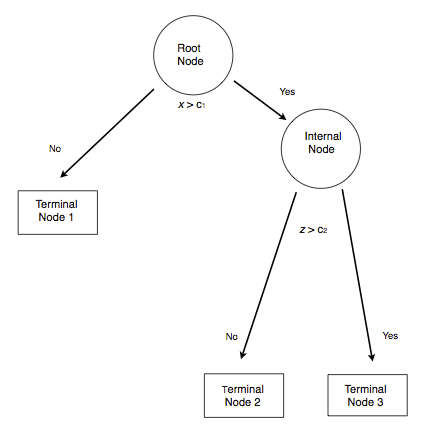

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Bayesian and Predictive Analysis ## DATA 606 - Statistics & Probability for Data Analytics ### Jason Bryer, Ph.D., Angela Lui, Ph.D., and George Hagstrom, Ph.D. ### December 4, 2024 --- # One Minute Paper Results .pull-left[ **What was the most important thing you learned during this class?** <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-2-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ **What important question remains unanswered for you?** <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-3-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- # Bayesian Analysis <img src='http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/515eRFg9Y8L._SX404_BO1,204,203,200_.jpg' align='right'> Kruschke's videos are an excelent introduction to Bayesian Analysis [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyohWpjl6KU](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyohWpjl6KU)! [Doing Bayesian Data Analysis, Second Edition: A Tutorial with R, JAGS, and Stan](http://www.amazon.com/Doing-Bayesian-Data-Analysis-Second/dp/0124058884/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1437688316&sr=8-1&keywords=Kruschke) *The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes' Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant from Two Centuries of Controversy* by Sharon Bertsch McGrayne Video series by Rasmus Baath [Part 1](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3OJEae7Qb_o&app=desktop), [Part 2](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mAUwjSo5TJE), [Part 3](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ie-6H_r7I5A) [Billiards with Fred the Frequentist and Bayer the Bayesian](https://towardsdatascience.com/billiards-with-fred-the-frequentist-and-bayer-the-bayesian-bayer-wins-7bc95b24a7ef) --- # Bayes Theorem $$ P(A|B)=\frac{P(B|A)P(A)}{P(B|A)P(A)+P(B|{A}^{'})P({A}^{'})} $$ Consider the following data from a cancer test: * 1% of women have breast cancer (and therefore 99% do not). * 80% of mammograms detect breast cancer when it is there (and therefore 20% miss it). * 9.6% of mammograms detect breast cancer when it's not there (and therefore 90.4% correctly return a negative result). | Cancer (1%) | No Cancer (99%) --------------|-------------|----------------- Test postive | 80% | 9.6% Test negative | 20% | 90.4% --- # How accurate is the test? Now suppose you get a positive test result. What are the chances you have cancer? 80%? 99%? 1%? * Ok, we got a positive result. It means we're somewhere in the top row of our table. Let's not assume anything - it could be a true positive or a false positive. * The chances of a true positive = chance you have cancer * chance test caught it = 1% * 80% = .008 * The chances of a false positive = chance you don't have cancer * chance test caught it anyway = 99% * 9.6% = 0.09504 | Cancer (1%) | No Cancer (99%) | --------------|-------------------|----------------------|------------- Test postive | True +: 1% * 80% | False +: 99% * 9.6% | **10.304%** Test negative | False -: 1% * 20% | True -: 99% * 90.4% | **89.696%** --- # How accurate is the test? $$ Probability = \frac{desired\quad event}{all\quad possibilities} $$ The chance of getting a real, positive result is .008. The chance of getting any type of positive result is the chance of a true positive plus the chance of a false positive (.008 + 0.09504 = .10304). `$$P(C | P) = \frac{P(P|C) P(C)}{P(P)} = \frac{.8 * .01}{.008 + 0.095} \approx .078$$` **So, our chance of cancer is .008/.10304 = 0.0776, or about 7.8%.** --- # Bayes Formula It all comes down to the chance of a true positive result divided by the chance of any positive result. We can simplify the equation to: $$ P\left( A|B \right) =\frac { P\left( B|A \right) P\left( A \right) }{ P\left( B \right) } $$ --- class: middle, center <img src='images/Bayes_Theorem_web.png' height='90%' /> --- # How many fish are in the lake? * Catch them all, count them. Not practical (or even possible)! * We can sample some fish. Our strategy: 1. Catch some fish. 2. Mark them. 3. Return the fish to the pond. Let them get mixed up (i.e. wait a while). 4. Catch some more fish. 5. Count how many are marked. For example, we initially caught 20 fish, marked them, returned them to the pond. We then caught another 20 fish and 5 of them were marked (i.e they were caught the first time). <font size='-1'> Adopted from Rasmath Bääth useR! 2015 workshop: http://www.sumsar.net/files/academia/user_2015_tutorial_bayesian_data_analysis_short_version.pdf </font> --- # Strategy for fitting a model Step 1: Define Prior Distribution. Draw a lot of random samples from the "prior" probability distribution on the parameters. ``` r n_draw <- 100000 n_fish <- sample(20:250, n_draw, replace = TRUE) head(n_fish, n=10) ``` ``` ## [1] 232 33 194 237 116 40 210 168 247 209 ``` ``` r hist(n_fish, main="Prior Distribution") ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-4-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Strategy for fitting a model Step 2: Plug in each draw into the generative model which generates "fake" data. ``` r pick_fish <- function(n_fish) { # The generative model fish <- rep(0:1, c(n_fish - 20, 20)) sum(sample(fish, 20)) } n_marked <- rep(NA, n_draw) for(i in 1:n_draw) { n_marked[i] <- pick_fish(n_fish[i]) } head(n_marked, n=10) ``` ``` ## [1] 0 14 2 2 4 10 2 4 0 2 ``` --- # Strategy for fitting a model Step 3: Keep only those parameter values that generated the data that was actually observed (in this case, 5). ``` r post_fish <- n_fish[n_marked == 5] hist(post_fish, main='Posterior Distribution') abline(v=median(post_fish), col='red') abline(v=quantile(post_fish, probs=c(.25, .75)), col='green') ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-6-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # What if we have better prior information? An "expert" believes there are around 200 fish in the pond. Insteand of a uniform distribution, we can use a binomial distribution to define our "prior" distribution. ``` r n_fish <- rnbinom(n_draw, mu = 200 - 20, size = 4) + 20 hist(n_fish, main='Prior Distribution') ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-7-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # What if we have better prior information? ``` r n_marked <- rep(NA, n_draw) for(i in 1:n_draw) { n_marked[i] <- pick_fish(n_fish[i]) } post_fish <- n_fish[n_marked == 5] hist(post_fish, main='Posterior Distribution') abline(v=median(post_fish), col='red') abline(v=quantile(post_fish, probs=c(.25, .75)), col='green') ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-8-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Bayes Billiards Balls Consider a pool table of length one. An 8-ball is thrown such that the likelihood of its stopping point is uniform across the entire table (i.e. the table is perfectly level). The location of the 8-ball is recorded, but not known to the observer. Subsequent balls are thrown one at a time and all that is reported is whether the ball stopped to the left or right of the 8-ball. Given only this information, what is the position of the 8-ball? How does the estimate change as more balls are thrown and recorded? ``` r DATA606::shiny_demo('BayesBilliards', package='DATA606') ``` See also: http://www.bryer.org/post/2016-02-21-bayes_billiards_shiny/ --- class: inverse, middle, center # Predictive Modeling --- # Example: Hours Studying Predicting Passing ``` r study <- data.frame( Hours=c(0.50,0.75,1.00,1.25,1.50,1.75,1.75,2.00,2.25,2.50,2.75,3.00, 3.25,3.50,4.00,4.25,4.50,4.75,5.00,5.50), Pass=c(0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1,1,1,1,1,1) ) study[sample(nrow(study), 5),] ``` ``` ## Hours Pass ## 18 4.75 1 ## 6 1.75 0 ## 13 3.25 1 ## 14 3.50 0 ## 5 1.50 0 ``` ``` r tab <- describeBy(study$Hours, group = study$Pass, mat = TRUE, skew = FALSE) tab$group1 <- as.integer(as.character(tab$group1)) ``` --- # Prediction Odds (or probability) of passing if studied **zero** hours? `$$log(\frac{p}{1-p}) = -4.078 + 1.505 \times 0$$` `$$\frac{p}{1-p} = exp(-4.078) = 0.0169$$` `$$p = \frac{0.0169}{1.169} = .016$$` -- Odds (or probability) of passing if studied **4** hours? `$$log(\frac{p}{1-p}) = -4.078 + 1.505 \times 4$$` `$$\frac{p}{1-p} = exp(1.942) = 6.97$$` `$$p = \frac{6.97}{7.97} = 0.875$$` --- # Fitted Values ``` r study[1,] ``` ``` ## Hours Pass ## 1 0.5 0 ``` ``` r logistic <- function(x, b0, b1) { return(1 / (1 + exp(-1 * (b0 + b1 * x)) )) } logistic(.5, b0=-4.078, b1=1.505) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.03470667 ``` --- # Model Performance The use of statistical models to predict outcomes, typically on new data, is called predictive modeling. Logistic regression is a common statistical procedure used for prediction. We will utilize a **confusion matrix** to evaluate accuracy of the predictions. <img src="images/Confusion_Matrix.png" width="1100" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: font80 # Predicting Heart Attacks Source: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/imnikhilanand/heart-attack-prediction?select=data.csv ``` r heart <- read.csv('../course_data/heart_attack_predictions.csv') heart <- heart |> mutate_if(is.character, as.numeric) |> select(!c(slope, ca, thal)) str(heart) ``` ``` ## 'data.frame': 294 obs. of 11 variables: ## $ age : int 28 29 29 30 31 32 32 32 33 34 ... ## $ sex : int 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 ... ## $ cp : int 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 3 2 ... ## $ trestbps: num 130 120 140 170 100 105 110 125 120 130 ... ## $ chol : num 132 243 NA 237 219 198 225 254 298 161 ... ## $ fbs : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ... ## $ restecg : num 2 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 ... ## $ thalach : num 185 160 170 170 150 165 184 155 185 190 ... ## $ exang : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ... ## $ oldpeak : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ... ## $ num : int 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ... ``` Note: `num` is the diagnosis of heart disease (angiographic disease status) (i.e. Value 0: < 50% diameter narrowing -- Value 1: > 50% diameter narrowing) --- # Missing Data We will save this for another day... ``` r complete.cases(heart) |> table() ``` ``` ## ## FALSE TRUE ## 33 261 ``` ``` r mice_out <- mice::mice(heart, m = 1) ``` ``` ## ## iter imp variable ## 1 1 trestbps chol fbs restecg thalach exang ## 2 1 trestbps chol fbs restecg thalach exang ## 3 1 trestbps chol fbs restecg thalach exang ## 4 1 trestbps chol fbs restecg thalach exang ## 5 1 trestbps chol fbs restecg thalach exang ``` ``` r heart <- mice::complete(mice_out) ``` --- # Data Setup We will split the data into a training set (70% of observations) and validation set (30%). ``` r train.rows <- sample(nrow(heart), nrow(heart) * .7) heart_train <- heart[train.rows,] heart_test <- heart[-train.rows,] ``` This is the proportions of survivors and defines what our "guessing" rate is. That is, if we guessed no one had a heart attack, we would be correct 62% of the time. ``` r (heart_attack <- table(heart_train$num) %>% prop.table) ``` ``` ## ## 0 1 ## 0.6731707 0.3268293 ``` --- class: font80 # Model Training ``` r lr.out <- glm(num ~ ., data=heart_train, family=binomial(link = 'logit')) summary(lr.out) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## glm(formula = num ~ ., family = binomial(link = "logit"), data = heart_train) ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|) ## (Intercept) -5.410691 3.302070 -1.639 0.101302 ## age 0.015795 0.033653 0.469 0.638825 ## sex 1.316689 0.548536 2.400 0.016379 * ## cp 0.901443 0.250571 3.598 0.000321 *** ## trestbps -0.008359 0.013372 -0.625 0.531906 ## chol 0.008494 0.003129 2.715 0.006637 ** ## fbs 0.644521 1.005240 0.641 0.521418 ## restecg -0.467020 0.652454 -0.716 0.474121 ## thalach -0.014209 0.011256 -1.262 0.206805 ## exang 1.121619 0.537306 2.087 0.036844 * ## oldpeak 1.130844 0.317328 3.564 0.000366 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1) ## ## Null deviance: 259.08 on 204 degrees of freedom ## Residual deviance: 140.00 on 194 degrees of freedom ## AIC: 162 ## ## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 6 ``` --- # Predicted Values ``` r heart_train$prediction <- predict(lr.out, type = 'response', newdata = heart_train) ggplot(heart_train, aes(x = prediction, color = num == 1)) + geom_density() ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-18-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Results ``` r heart_train$prediction_class <- heart_train$prediction > 0.5 tab <- table(heart_train$prediction_class, heart_train$num) %>% prop.table() %>% print() ``` ``` ## ## 0 1 ## FALSE 0.61463415 0.08780488 ## TRUE 0.05853659 0.23902439 ``` For the training set, the overall accuracy is 85.37%. Recall that 67.32% people did not have a heart attach. Therefore, the simplest model would be to predict that no one had a heart attack, which would mean we would be correct 67.32% of the time. Therefore, our prediction model is 18.05% better than guessing. --- # Checking with the validation dataset ``` r (survived_test <- table(heart_test$num) %>% prop.table()) ``` ``` ## ## 0 1 ## 0.5617978 0.4382022 ``` ``` r heart_test$prediction <- predict(lr.out, newdata = heart_test, type = 'response') heart_test$prediciton_class <- heart_test$prediction > 0.5 tab_test <- table(heart_test$prediciton_class, heart_test$num) %>% prop.table() %>% print() ``` ``` ## ## 0 1 ## FALSE 0.50561798 0.11235955 ## TRUE 0.05617978 0.32584270 ``` The overall accuracy is 83.15%, or 27% better than guessing. --- class: font90 # Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve The ROC curve is created by plotting the true positive rate (TPR; AKA sensitivity) against the false positive rate (FPR; AKA probability of false alarm) at various threshold settings. .pull-left[ In a classification model, outcomes are either as positive (*p*) or negative (*n*). There are then four possible outcomes: * **true positive** (TP) The outcome from a prediction is *p* and the actual value is also *p*. * **false positive** (FP) The actual value is *n*. * **true negative** (TN) Both the prediction outcome and the actual value are *n*. * **false negative** (FN) The prediction outcome is *n* while the actual value is *p*. ] .pull-right[  ``` r roc <- calculate_roc(heart_train$prediction, heart_train$num == 1) summary(roc) ``` ``` ## AUC = 0.915 ## Cost of false-positive = 1 ## Cost of false-negative = 1 ## Threshold with minimum cost = 0.515 ``` ] --- # ROC Curve .center[  ] --- # ROC Curve ``` r plot(roc, curve = 'accuracy') ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-22-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # ROC Curve ``` r plot(roc) ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-23-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: font90 # Caution on Interpreting Accuracy - [Loh, Sooo, and Zing](http://cs229.stanford.edu/proj2016/report/LohSooXing-PredictingSexualOrientationBasedOnFacebookStatusUpdates-report.pdf) (2016) predicted sexual orientation based on Facebook Status. - They reported model accuracies of approximately 90% using SVM, logistic regression and/or random forest methods. -- - [Gallup](https://news.gallup.com/poll/234863/estimate-lgbt-population-rises.aspx) (2018) poll estimates that 4.5% of the Americal population identifies as LGBT. -- - *My proposed model:* I predict all Americans are heterosexual. - The accuracy of my model is 95.5%, or *5.5% better than Facebook's model!* - Predicting "rare" events (i.e. when the proportion of one of the two outcomes large) is difficult and requires independent (predictor) variables that strongly associated with the dependent (outcome) variable. --- # Fitted Values Revisited What happens when the ratio of true-to-false increases (i.e. want to predict "rare" events)? Let's simulate a dataset where the ratio of true-to-false is 10-to-1. We can also define the distribution of the dependent variable. Here, there is moderate separation in the distributions. ``` r test.df2 <- getSimulatedData( treat.mean=.6, control.mean=.4) ``` The `multilevelPSA::psrange` function will sample with varying ratios from 1:10 to 1:1. It takes multiple samples and averages the ranges and distributions of the fitted values from logistic regression. ``` r psranges2 <- psrange(test.df2, test.df2$treat, treat ~ ., samples=seq(100,1000,by=100), nboot=20) ``` --- # Fitted Values Revisited (cont.) ``` r plot(psranges2) ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-27-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: left, font140 # One Minute Paper .pull-left[ 1. What was the most important thing you learned during this class? 2. What important question remains unanswered for you? ] .pull-right[ <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-28-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] https://forms.gle/ESBAdHRhzT65fW6c6 --- class: middle, center, inverse # BONUS: Classification and Regression Trees --- # Classification and Regression Trees The goal of CART methods is to find best predictor in X of some outcome, y. CART methods do this recursively using the following procedures: * Find the best predictor in X for y. * Split the data into two based upon that predictor. * Repeat 1 and 2 with the split data sets until a stopping criteria has been reached. There are a number of possible stopping criteria including: Only one data point remains. * All data points have the same outcome value. * No predictor can be found that sufficiently splits the data. --- # Recursive Partitioning Logic of CART .pull-left[ Consider the scatter plot to the right with the following characteristics: * Binary outcome, G, coded “A” or “B”. * Two predictors, x and z * The vertical line at z = 3 creates the first partition. * The double horizontal line at x = -4 creates the second partition. * The triple horizontal line at x = 6 creates the third partition. ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Tree Structure .pull-left[ * The root node contains the full data set. * The data are split into two mutually exclusive pieces. Cases where x > ci go to the right, cases where x <= ci go to the left. * Those that go to the left reach a terminal node. * Those on the right are split into two mutually exclusive pieces. Cases where z > c2 go to the right and terminal node 3; cases where z <= c2 go to the left and terminal node 2. ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Sum of Squared Errors The sum of squared errors for a tree *T* is: `$$S=\sum _{ c\in leaves(T) }^{ }{ \sum _{ i\in c }^{ }{ { (y-{ m }_{ c }) }^{ 2 } } }$$` Where, `\({ m }_{ c }=\frac { 1 }{ n } \sum _{ i\in c }^{ }{ { y }_{ i } }\)`, the prediction for leaf \textit{c}. Or, alternatively written as: `$$S=\sum _{ c\in leaves(T) }^{ }{ { n }_{ c }{ V }_{ c } }$$` Where `\(V_{c}\)` is the within-leave variance of leaf \textit{c}. Our goal then is to find splits that minimize S. --- # Advantages of CART Methods * Making predictions is fast. * It is easy to understand what variables are important in making predictions. * Trees can be grown with data containing missingness. For rows where we cannot reach a leaf node, we can still make a prediction by averaging the leaves in the sub-tree we do reach. * The resulting model will inherently include interaction effects. There are many reliable algorithms available. --- # Regression Trees In this example we will predict the median California house price from the house’s longitude and latitude. ``` r str(calif) ``` ``` ## 'data.frame': 20640 obs. of 10 variables: ## $ MedianHouseValue: num 452600 358500 352100 341300 342200 ... ## $ MedianIncome : num 8.33 8.3 7.26 5.64 3.85 ... ## $ MedianHouseAge : num 41 21 52 52 52 52 52 52 42 52 ... ## $ TotalRooms : num 880 7099 1467 1274 1627 ... ## $ TotalBedrooms : num 129 1106 190 235 280 ... ## $ Population : num 322 2401 496 558 565 ... ## $ Households : num 126 1138 177 219 259 ... ## $ Latitude : num 37.9 37.9 37.9 37.9 37.9 ... ## $ Longitude : num -122 -122 -122 -122 -122 ... ## $ cut.prices : Factor w/ 4 levels "[1.5e+04,1.2e+05]",..: 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 ... ``` --- # Tree 1 ``` r treefit <- tree(log(MedianHouseValue) ~ Longitude + Latitude, data=calif) plot(treefit); text(treefit, cex=0.75) ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-30-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Tree 1 <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-31-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Tree 1 ``` r summary(treefit) ``` ``` ## ## Regression tree: ## tree(formula = log(MedianHouseValue) ~ Longitude + Latitude, ## data = calif) ## Number of terminal nodes: 12 ## Residual mean deviance: 0.1662 = 3429 / 20630 ## Distribution of residuals: ## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. ## -2.75900 -0.26080 -0.01359 0.00000 0.26310 1.84100 ``` Here “deviance” is the mean squared error, or root-mean-square error of `\(\sqrt{.166} = 0.41\)`. --- # Tree 2, Reduce Minimum Deviance We can increase the fit but changing the stopping criteria with the mindev parameter. ``` r treefit2 <- tree(log(MedianHouseValue) ~ Longitude + Latitude, data=calif, mindev=.001) summary(treefit2) ``` ``` ## ## Regression tree: ## tree(formula = log(MedianHouseValue) ~ Longitude + Latitude, ## data = calif, mindev = 0.001) ## Number of terminal nodes: 68 ## Residual mean deviance: 0.1052 = 2164 / 20570 ## Distribution of residuals: ## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. ## -2.94700 -0.19790 -0.01872 0.00000 0.19970 1.60600 ``` With the larger tree we now have a root-mean-square error of 0.32. --- # Tree 2, Reduce Minimum Deviance <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-34-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Tree 3, Include All Variables However, we can get a better fitting model by including the other variables. ``` r treefit3 <- tree(log(MedianHouseValue) ~ ., data=calif) summary(treefit3) ``` ``` ## ## Regression tree: ## tree(formula = log(MedianHouseValue) ~ ., data = calif) ## Variables actually used in tree construction: ## [1] "cut.prices" ## Number of terminal nodes: 4 ## Residual mean deviance: 0.03608 = 744.5 / 20640 ## Distribution of residuals: ## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. ## -1.718000 -0.127300 0.009245 0.000000 0.130000 0.358600 ``` With all the available variables, the root-mean-square error is 0.11. --- # Classification Trees Predicting who survived the Titanic. * `pclass`: Passenger class (1 = 1st; 2 = 2nd; 3 = 3rd) * `survival`: A Boolean indicating whether the passenger survived or not (0 = No; 1 = Yes); this is our target * `name`: A field rich in information as it contains title and family names * `sex`: male/female * `age`: Age, a significant portion of values are missing * `sibsp`: Number of siblings/spouses aboard * `parch`: Number of parents/children aboard * `ticket`: Ticket number. * `fare`: Passenger fare (British Pound). * `cabin`: Does the location of the cabin influence chances of survival? * `embarked`: Port of embarkation (C = Cherbourg; Q = Queenstown; S = Southampton) * `boat`: Lifeboat, many missing values * `body`: Body Identification Number * `home.dest`: Home/destination --- # Classification using `rpart` ``` r (titanic.rpart <- rpart(survived ~ pclass + sex + age + sibsp, data=titanic.train)) ``` ``` ## n= 981 ## ## node), split, n, deviance, yval ## * denotes terminal node ## ## 1) root 981 231.6514000 0.38226300 ## 2) sex=male 630 94.0079400 0.18253970 ## 4) age>=9.5 595 80.5109200 0.16134450 ## 8) pclass>=1.5 464 50.7500000 0.12500000 * ## 9) pclass< 1.5 131 26.9771000 0.29007630 * ## 5) age< 9.5 35 8.6857140 0.54285710 ## 10) sibsp>=2.5 13 0.9230769 0.07692308 * ## 11) sibsp< 2.5 22 3.2727270 0.81818180 * ## 3) sex=female 351 67.4074100 0.74074070 ## 6) pclass>=2.5 159 39.5597500 0.53459120 ## 12) sibsp>=2.5 18 2.5000000 0.16666670 * ## 13) sibsp< 2.5 141 34.3120600 0.58156030 * ## 7) pclass< 2.5 192 15.4947900 0.91145830 * ``` --- # Classification using `rpart` ``` r plot(titanic.rpart); text(titanic.rpart, use.n=TRUE, cex=1) ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-37-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Classification using `ctree` ``` r (titanic.ctree <- ctree(survived ~ pclass + sex + age + sibsp, data=titanic.train)) ``` ``` ## ## Conditional inference tree with 9 terminal nodes ## ## Response: survived ## Inputs: pclass, sex, age, sibsp ## Number of observations: 981 ## ## 1) sex == {female}; criterion = 1, statistic = 297.133 ## 2) pclass <= 2; criterion = 1, statistic = 63.869 ## 3) pclass <= 1; criterion = 0.966, statistic = 6.906 ## 4)* weights = 114 ## 3) pclass > 1 ## 5)* weights = 78 ## 2) pclass > 2 ## 6) sibsp <= 2; criterion = 0.993, statistic = 9.706 ## 7)* weights = 141 ## 6) sibsp > 2 ## 8)* weights = 18 ## 1) sex == {male} ## 9) pclass <= 1; criterion = 0.999, statistic = 12.655 ## 10) age <= 54; criterion = 0.958, statistic = 6.517 ## 11)* weights = 107 ## 10) age > 54 ## 12)* weights = 27 ## 9) pclass > 1 ## 13) age <= 9; criterion = 1, statistic = 15.073 ## 14) sibsp <= 2; criterion = 0.999, statistic = 13.965 ## 15)* weights = 19 ## 14) sibsp > 2 ## 16)* weights = 13 ## 13) age > 9 ## 17)* weights = 464 ``` --- # Classification using `ctree` ``` r plot(titanic.ctree) ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-39-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Ensemble Methods Ensemble methods use multiple models that are combined by weighting, or averaging, each individual model to provide an overall estimate. Each model is a random sample of the sample. Common ensemble methods include: * *Boosting* - Each successive trees give extra weight to points incorrectly predicted by earlier trees. After all trees have been estimated, the prediction is determined by a weighted “vote” of all predictions (i.e. results of each individual tree model). * *Bagging* - Each tree is estimated independent of other trees. A simple “majority vote” is take for the prediction. * *Random Forests* - In addition to randomly sampling the data for each model, each split is selected from a random subset of all predictors. * *Super Learner* - An ensemble of ensembles. See https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SuperLearner/vignettes/Guide-to-SuperLearner.html --- class: font90 # Random Forests The random forest algorithm works as follows: 1. Draw `\(n_{tree}\)` bootstrap samples from the original data. 2. For each bootstrap sample, grow an unpruned tree. At each node, randomly sample `\(m_{try}\)` predictors and choose the best split among those predictors selected<footnote>Bagging is a special case of random forests where `\(m_{try} = p\)` where *p* is the number of predictors</footnote>. 3. Predict new data by aggregating the predictions of the ntree trees (majority votes for classification, average for regression). Error rates are obtained as follows: 1. At each bootstrap iteration predict data not in the bootstrap sample (what Breiman calls “out-of-bag”, or OOB, data) using the tree grown with the bootstrap sample. 2. Aggregate the OOB predictions. On average, each data point would be out-of-bag 36% of the times, so aggregate these predictions. The calculated error rate is called the OOB estimate of the error rate. --- # Random Forests: Titanic ``` r titanic.rf <- randomForest(factor(survived) ~ pclass + sex + age + sibsp, data = titanic.train, ntree = 5000, importance = TRUE) ``` ``` r importance(titanic.rf) ``` ``` ## 0 1 MeanDecreaseAccuracy MeanDecreaseGini ## pclass 85.09022 118.70848 128.7378 47.68747 ## sex 228.40719 264.64554 278.5036 122.30795 ## age 92.56967 43.31360 110.2096 56.32722 ## sibsp 78.95009 -10.49729 61.6449 17.40713 ``` --- # Random Forests: Titanic (cont.) ``` r importance(titanic.rf) ``` ``` ## 0 1 MeanDecreaseAccuracy MeanDecreaseGini ## pclass 85.09022 118.70848 128.7378 47.68747 ## sex 228.40719 264.64554 278.5036 122.30795 ## age 92.56967 43.31360 110.2096 56.32722 ## sibsp 78.95009 -10.49729 61.6449 17.40713 ``` --- # Random Forests: Titanic ``` r min_depth_frame <- min_depth_distribution(titanic.rf) ``` ``` r plot_min_depth_distribution(min_depth_frame) ``` <img src="10-Bayesian_Analysis_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-42-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" />